THE BEST METHODS AND APPROACH FOR DETERMINING QUANTUM MATTERS ARE:

- The use of a sophisticated cost system that allows an audit trail of cause, effect, and entitlement.

- In the absence of a sophisticated system, the use of the records available should be the next alternative, for example invoices, payslips, diaries, etc. In a digital world it is sometimes difficult to understand the inability to satisfy the interrelation between records and costs, particularly when both parties understand the nature of the contract and how it will likely be performed.

- In the absence of either, and where the claiming party uses a global approach due to a genuine inability to extract cost information from its records, the parties should consider the background circumstances which explain the genesis and purpose of the contract, how records should have been collated, and what should probably have been in the minds of the parties when they contracted. If a genuine inability to produce the records to a satisfactory level exists and is accepted, the two experts need to act pragmatically.

The Interpretation of Quantum

Damian James provides a South African perspective, reviews the ‘balance of probabilities’ approach to expert evidence, and outlines the experts’ obligations to court or tribunal.

Previously, this area of the law was predictable and would warrant a detailed analysis of submissions made to a tribunal. However, there has been a significant shift in the approach to the interpretation of quantum. Particularly where a tribunal has decided liability and where jurisdiction allows for a test on a ‘balance of probabilities’ basis.

Before, the test for determining all quantum issues was an audit trail of paperwork, diaries, invoices, certificates, bank statements, and the like.. Nowadays the pragmatic nature of determining costs, following attributing liability to a particular party, is in the hands and remit of the experts representing the parties.

In this respect, the experts need to have regard to surrounding circumstances and avoid any ambiguous evidence. They do so by considering the submissions and exchanges between the parties. The experts should use all evidence available to determine a ‘balance of probabilities’ resolution on the quantum due. This would satisfy their duty to the tribunal.

The resolution and agreement of costs will very much rely on the experts’ willingness to accept that ‘a balance of probabilities’ is the best method for resolution. The tribunal will have decided on liability and the method to be used, leaving the experts instructed to resolve quantum.

The ‘balance of probabilities’ can be determined by a matrix weighting of the evidence by the experts. Two pragmatic and experienced individuals should certainly be capable of such an interlocutory. The experts could give a weighting to particular records and evidence and, where the weighting exceeds 51%, the ‘balance of probabilities‘ test can be said to have been satisfied. The experts can then agree a ’figure as a figure’ without having to consider their preferred method of substantiating the costs.

But, what would prevent the experts from agreeing? Are these tasks time consuming and laborious?

The experts have a role to fulfil and can make this process succeed or fail:

- a) Success is about the experts’ willingness, their experience of such matters, the ability to sensibly interpret the evidence, and a desire to exercise their duty to the tribunal.

- b) Failure is about the experts’ lack of cooperation and unwillingness to agree large or small issues. A desire for one up-manship by opening up unrelated areas to discussion, or a want to impress the tribunal and others with misleading answers on law or conjecture riddled statements. A reliance on pedantic observations and criticisms, a lack of commercial acumen, insecurity as to their own vanity, or the partisan approach of the experts represented as a hired gun or gunslinger referred to in this article.

The experts’ duty is to the tribunal, they affirm such a statement in their reports, and they are not in the role:

- for vanity, notoriety, or stardom

- to impress the tribunal with their effusive love of the English language

- to detract from the tribunal’s ambitions

- to maximise the benefit to their own client

In concluding the above, it is worth considering a number of cases, three from South Africa and two from the UK.

In South African law, there is a distinction between the admissibility and the probative value of an expert’s opinion. Simply put, the tribunal has to decide whether the expert’s submission is of any use to the issues before it. The procedural requirements of such submissions have been aligned and corrected by the requirements listed at law, but this issue of probative value remains undetermined.

In the Mashile 1993 (2) SACR 67 (A), an expert’s opinion was found to be inadequate despite him providing an abundance of details on speeds, distances, and ranges of visibility.

Whereas in Nksatlala 1960 (3) SA 543 (A) 546, Schreiner JA provided the following insight:

“A court should not blindly accept and act upon the evidence of an expert witness, even of a fingerprint expert, but must decide for itself whether it can safely accept the expert’s opinion.”

In the matter between Vuyusile Eunice Lushaba and the MEC for health , Gauteng 2015, the defendant relied on an expert opinion that revealed no defence and had been made without the use of vital medical records. In an attempt to appeal the court’s original decision the defendant asked the court to ignore its expert’s evidence. In this instance the defendant maintained that it relied totally on the opinion of its expert. RM Robinson AJ saw the requirement to furnish the expert with records as the responsibility of the defendant, and they were responsible for the decision to proceed. Subsequently, the defendant’s leave to appeal the decision on such grounds was refused with costs.

Recently in the UK, her Honour Mrs Justice Cox made some important observations about the role of an expert witness and the conduct of the defendant’s expert in Sinclair -v- Joyner [2015] EWHC Civ 1800 (QB).

Briefly, the claimant, a cyclist, sustained serious injuries following a collision with a car driven by the defendant in a rural location. Mrs Justice Cox was to determine liability only in the subsequent hearing.

The parties gave oral evidence and both obtained reports from accident reconstruction experts to present.

Mrs Justice Cox found that the evidence given by the defendant’s expert was unsatisfactory in a number of respects and that the defendant’s expert had put forward evidence, “exceeding its proper parameters”.

As the trial concluded, the defendant’s counsel no longer relied upon the evidence put forward by its expert. In this case the expert had alleged that there had been no contact between the car and the bike, when clearly there had.

Mrs Justice Cox confirmed that the role of the expert in this case was to provide accident reconstruction evidence.

Mrs Justice Cox referred to the Court of Appeal decision in Liddell v Middleton [1996] PIQR P 36 and Lord Justice Stuart Smith’s definition of the expert’s role:

“…to provide the judge with the necessary scientific criteria and assistance based upon his or her specific skills and experience, which the lay judge will not usually possess, to enable the judge to interpret the factual evidence.”

Lord Justice Stuart Smith elaborated further, defining the role of such an expert was not:

“…to discover the facts and to use [their] expertise and experience to give an opinion as to what happened.”

Conclusion

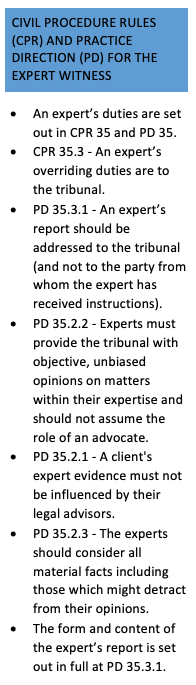

The expert has a role to fulfil and an obligation to the tribunal (see the CPR and PD explanations box). To maximise this, the expert should be provided with clear, precise instructions by their legal team so as to avoid coming under fire from the tribunal in respect of ‘exceeding their parameters’ as per the findings of Mrs Justice Cox in this case.

The tribunals that quantum experts stand before do not want, or need, lone rangers making a leap from the evidential requirements of a quantum report. If the expert works within the parameters set by the tribunal and avoids putting on their own show, then they have fulfilled their obligations to the tribunal. If they don’t, then the tribunal should ‘pull the curtain down’ on them, clients should recognise their gamesmanship and perhaps, next time, speak to the independent and experienced experts.

In the final analysis perhaps we should draw on the words of George Orwell:

“The great enemy of clear language is insincerity. When there is a gap between one’s real and one’s declared aims, one turns as it were instinctively to long words and exhausted idioms, like a cuttlefish spurting out ink.”