The Brief

If you find yourself involved in a dispute regarding the time aspects of your project, you may find that the appointment of a delay expert is an essential consideration to extract entitlement.

Delay analysis is arguably a difficult subject to deal with and one that many misunderstand. How do you know where to begin when selecting an expert?

Should the ability of the delay expert be of primary importance?

A well balanced and impartial expert ought to be able to take an interrogative approach to the commission. They should have the ability to trace and demonstrate causes and their effects throughout the project. In aiding the legal team in their understanding, they will provide valuable knowledge and guidance on the entitlement that is to be sought.

When you commission a delay expert you are asking them to provide an impartial and objective opinion on the validity and merits of delays suffered. If the delay expert can evidence entitlement to additional time, the appointing party ought to be able to rely on the expert’s findings.

You should expect your expert to discharge their role with specific diligence. A poor expert may use a formulaic and repetitive approach in each of their previous reports. If possible, examine such reports for generic or formulaic content.

The issues with delay experts

Delay experts are commonly wide ranging in ability. With the advent of computerised delay analysis, the days of the experienced old hand have reduced. What has arrived in their place is the project control analyst whose science provides the answer, or maybe it just causes the problem…

The delay analysis

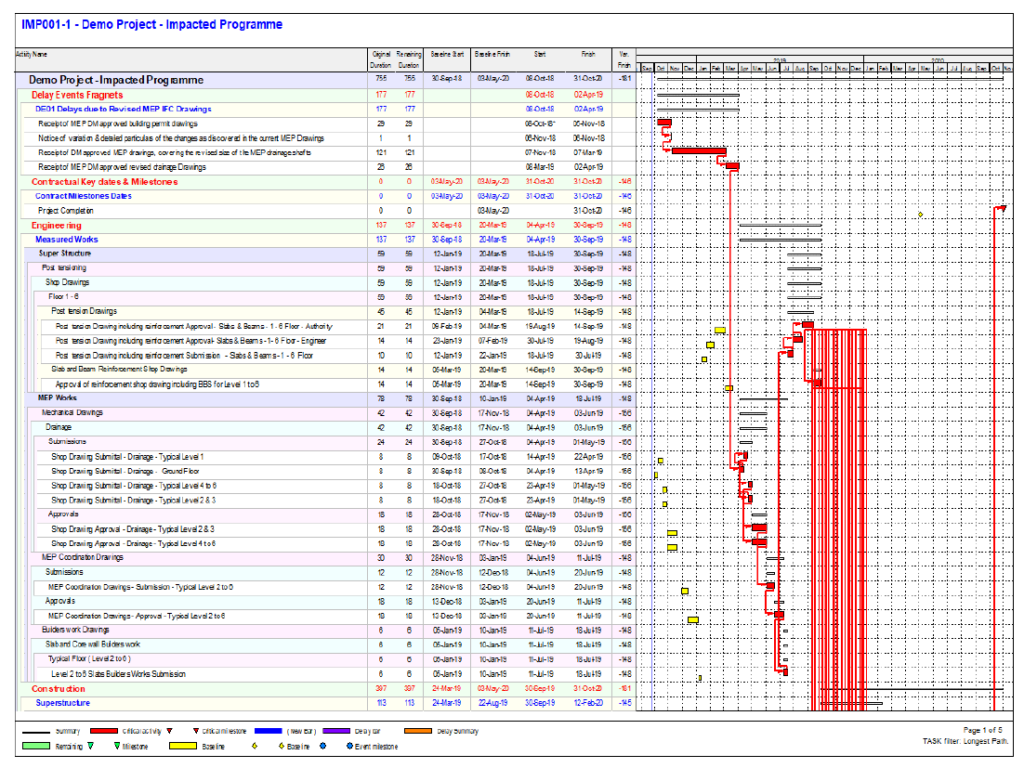

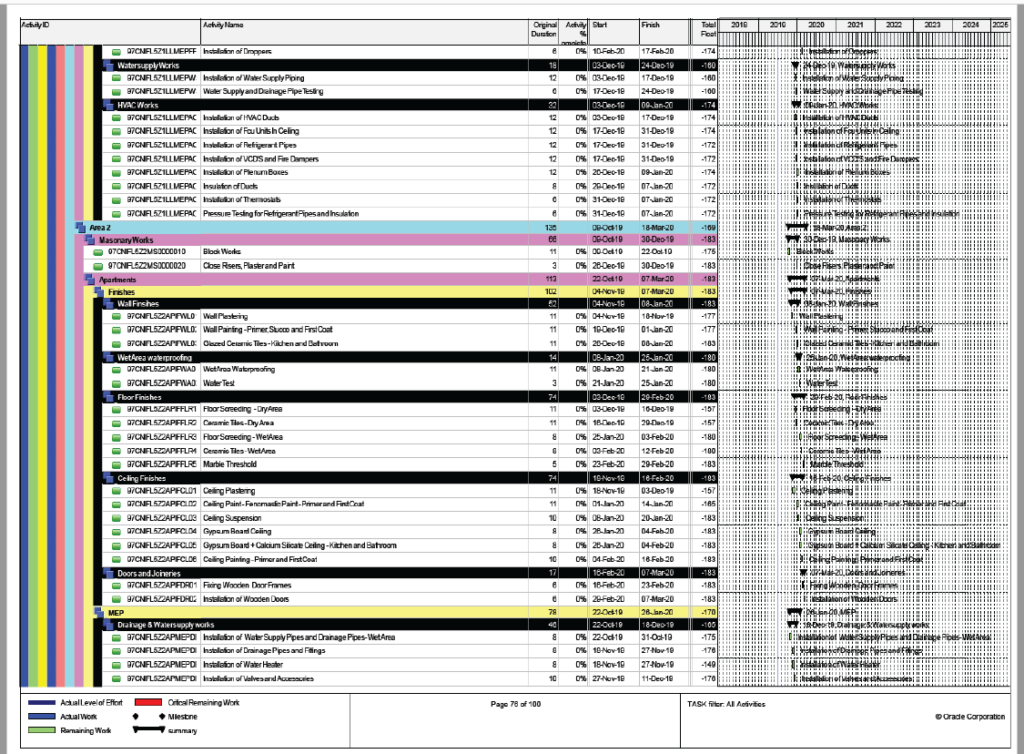

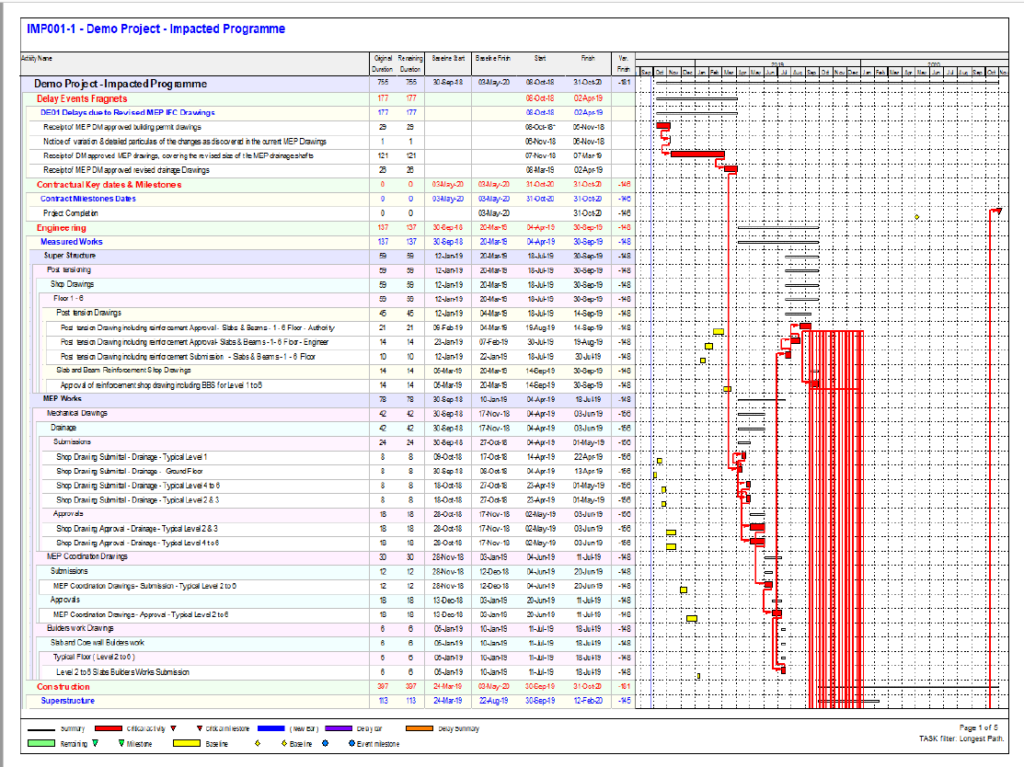

Delay analysis is commonly impressionistic or highly theoretical and often reliant on thousands of pages of A3 with green and red lines to demonstrate both float and critical paths.

Whilst the words in an export report should articulate the analysis performed, it is often the expert who is the only one understands the documents and how to interpret them. In examinaton, this may suit the expert.

The arbitrator will often find himself referred to page 2876 of the bundle, to activity 340. The arbitrator takes his magnifying glass and reads the words, ‘stakeholder 189 days’, before asking what does this mean?

In my experience what normally follows, is an enthusiastic explanation of windows analysis, concurrency, dominant delays, parallel delays and why the contractor has entitlement for a claim for an extension of time that bears little resemblance to the facts.

Add to this the necessary commentary on the Malmaison case, which dictates that a contractor is entitled to time but not money, and the entitlement is established.

When the impressionistic approach is divorced from the facts and contract terms, this form of analysis becomes blurry.

The application of facts and contractual merits cannot be disregarded. Often when considered against an impressionistic analysis, they will unpick the credibility of an expert report and the expert themselves.

It is often the case, in hearings, that when parties consider the evidence and facts presented by their opposition or by their own personnel, the realisation of the flaws and errors in their impressionistic analysis renders their probability of success weaker.

In my experience, the answer is usually within the documents. It is often the expert’s inability to extract the analysis from the project documents that causes failure.

Choice of Method

The first step for an expert to prove delay entitlement, is the understanding of the contract delay provisions. These may dictate the specific form of analysis, or define whether an analysis should be prospective or retrospective. At other times, the contract will be silent on the preferred method of analysis and it is up to the expert to decide which method to use.

There is much debate on the advantages of the different methods of delay analysis. It may seem as though each method ought to provide the same results – but this rarely happens. An expert must determine whether a contractor is prejudiced or indeed if causation is actually evidenced. They should start with the method that can be debated the strongest.

The practitioner must have regard to the total period of delay and those key periods when the delay occurred. A simple overview of as planned and as built illustrates this.

Regard to the Facts

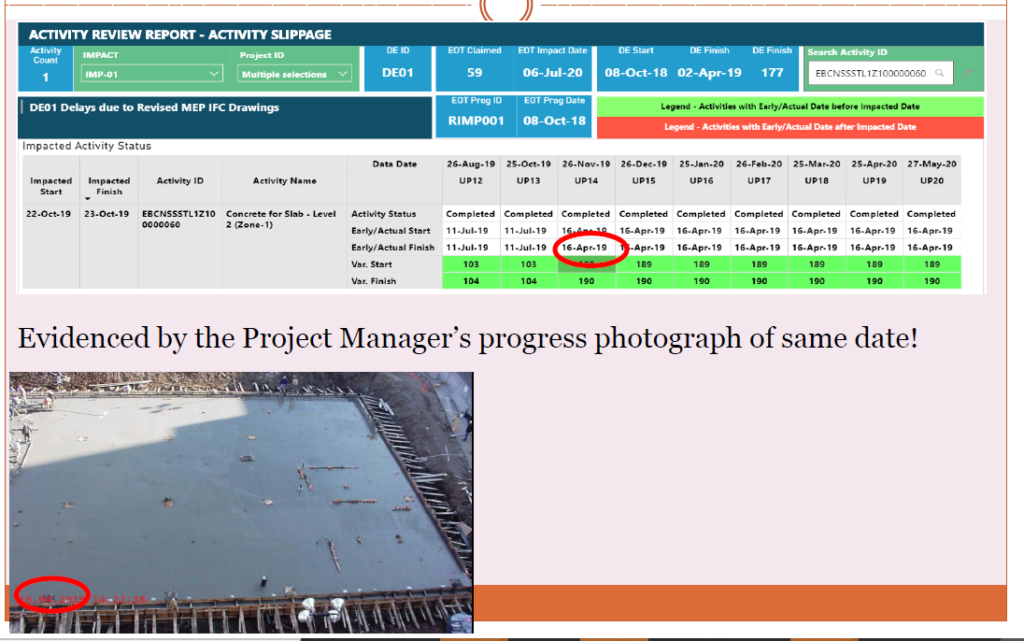

The delay events must be examined with regard to the facts. This will often be provided by factual witnesses and housed in their statements. It is a mistake to not test the facts against updated programmes and the project manager’s photographs of actual progress.

The expert who enters the hearing and begins to hear facts that do not corroborate with his impressionistic analysis only has one person to blame.

The next step for an expert is to identify the critical path. In doing so he must understand and explain the difficulties and reality of a project’s technical and physical challenges.

An arbitrator or tribunal often benefit from such explanation. In my experience, they will appreciate the inclusion of the more specific parts of the project in dispute.

However, there are some arbitrators may have little regard to critical path analysis. They will prefer the expert to consider cause and effect.

In identifying the delay events, the expert must prove that they caused an actual delay. If not, why focus on them? The delay to the completion date should be the concluding effect of these events.

The expert mustn’t stop here though, but sadly they often do. The expert should continue to consider delays in accordance with the relevant provisions and the contractual context.

The key components of this consideration are commonly recognisable but often not considered correctly by the expert in the context of the expert report. They include:

• Notices

• Time bars

• Risk ownership

• Apportionment of liability

• Concurrency

• Dominant delay

• But for

• Contract terms

In some instances, it may be that the expert is reluctant to enter the arena of merit and wishes to stay in the entitlement zone. There is nothing wrong with this approach but it may be beneficial to undertake a risk analysis of the entitlement when considered with the other legal issues.

The expert should not, however, endeavour to cloud these issues with impressionistic analysis and complex terms that they expect the arbitrator to be incapable of unravelling. They will be unravelled and there will be the very real danger of the opinion being rendered redundant in the proceedings.

It may be that experts feel bound by the software they are using. It can prohibit them from extracting the entitlement. Or it may be that the expert is simply more comfortable with an impressionistic approach to analysis.

In my experience, good data is often available to the expert. However a reliance on the ‘impressionistic’ approach by some experts thwarts their correct appropriation into the dispute.

Extracting Entitlement

To extract the entitlement, the expert must discount preconceptions and provide an analysis that represents the facts.

The methodology for the analysis must revolve around facts and common sense.

The information provided by a claimant or defendant should be collated chronologically and placed into a data bank that allows extraction for comparisons and analysis

When assimilated correctly the project information should be capable of demonstrating the entitlement. At the very least correctly incorporating and interpreting the facts within the analysis is key to successful extraction of entitlement.

The extraction

To avoid an impressionistic approach and ensure success, elements to consider when extracting entitlement in the analysis of delay should include all of the following:

- The notices.

- The measles chart.

- The windows delays.

- The accrued delays.

- The concurrent delays.

- The driving delay.

- The dominant delay.

- The photographs.

- The conclusion of the analysis relative to the facts and the supporting documents.

In the case that an analysis is carried out during the project lifecycle, it is key to comply with the requirements of the building contract by:

- Giving any applicable notices.

- Responding to requests for information by the architect/contract administrator.

- Prove the claim as a matter of fact on the balance of probabilities.

- Put forward enough evidence to substantiate its alleged losses.

- Show that it would not have incurred the alleged delay related losses in any event.

- Highlight any delays that are not the defendant’s responsibility.

- Separately plead any heads of claim where a demonstrable causal link can be proved.

When it goes wrong – A Worked Example

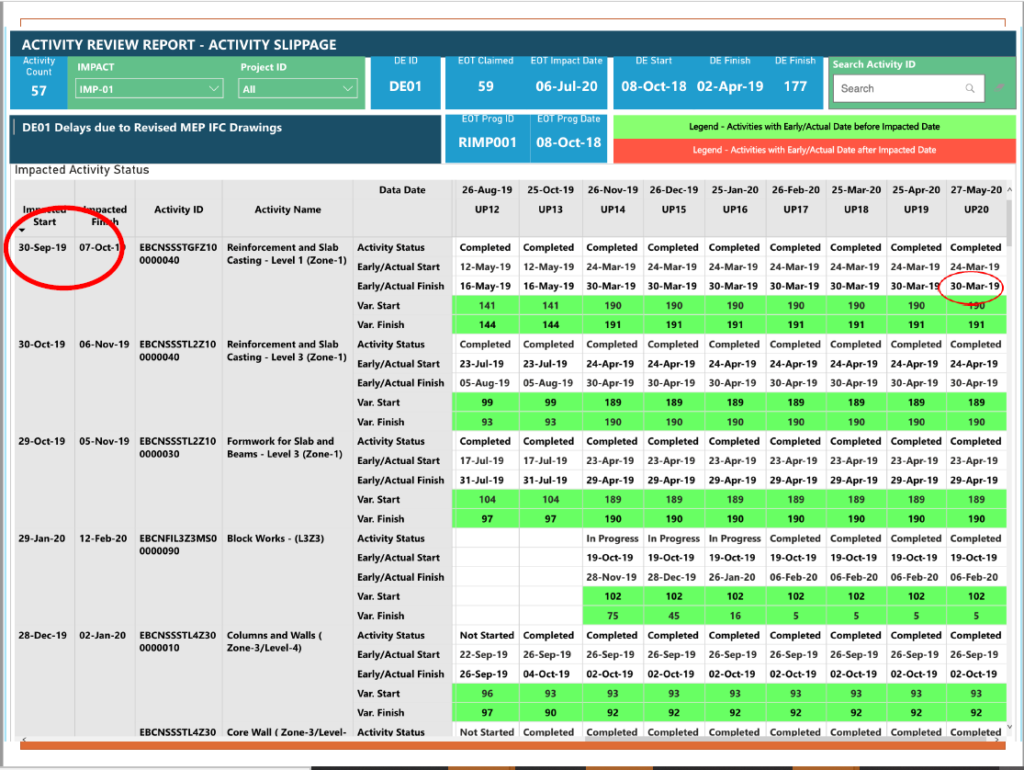

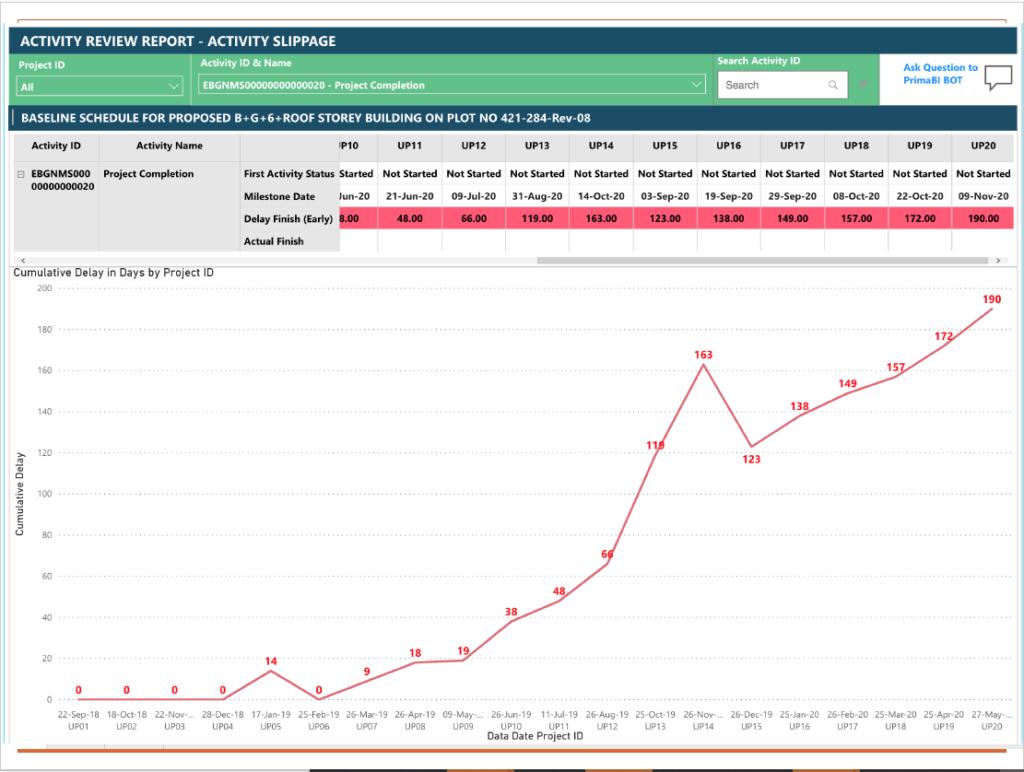

A retrospective analysis is provides time in slices / windows. These demonstrate the period gains or delays through a series of monthly, quarterly assessments.

However, a summary of the analysis often renders a conclusion that in 31 working days, a critical delay of 54 days was suffered.

For the arbitrator this raises questions.

In the next windows it may be that in 31 days, an improvement in the project completion of 66 days resulted.

The challenge for the arbitrator here is one of not only comprehension but of factual accountability.

If the project was in a severe delay (54 days) then where is the notice explaining this to be found?

The risk for the expert is that at this point he loses his audience and questions begin to be asked in the mind of the arbitrator on the very integrity of the report.

Often when this form of analysis is placed before the arbitrator, the algorithm reads that in 365 days of planned programme days, there were 365 delay days. The conundrum of every project day being a delay day is complex for even the most intuitive of minds.

The expert takes the approach of determining all of these delays and mitigations days to conclude in an overall delay at window 24 of 200 days.

The next erroneous algorithm that is placed before an arbitrator is that of accrued delay.

The window analysis evidences a delay of 200 days before window 25, at window 24 of the analysis. That is to say that the arbitrator understands that the delays in the prior period would have caused completion to be delayed by 200 days.

The facts and the notices ought to be able to evidence the causation of this delay. The witness statements ought to be able to suggest to the arbitrator the issues of causation that were faced by the claimant.

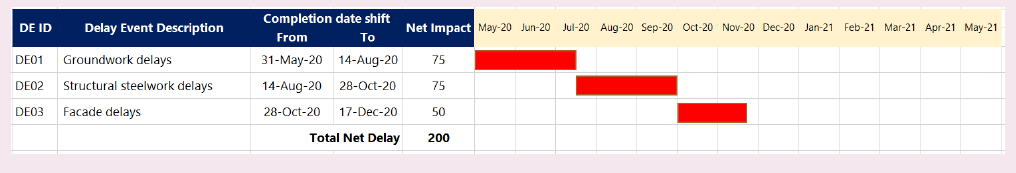

So, by analysis, the arbitrator may be able to understand the following causes:

| Groundwork delays | 75 days |

| Structural steelwork delays | 75 days |

| Facade delays | 50 days |

In the next phase of window analysis, the expert advises that the delay is reduced to 180 days. The causes of the delay are:

| Mechanical delays | 60 days |

| Electrical delays | 60 days |

| HVAC delays | 60 days |

In understanding the now whereabouts of the delays in the previous windows (the 200 days), the arbitrator may be provided with an explanation of dominancy and driving delays.

At this point, the arbitrator, relies on the expert to account for the delays caused by the first incumbents. As well as to explain this with regard to the second incumbents.

The added confusion here, is that the arbitrator is now advised to discount the delays caused by the first incumbents. And to attach the causation of the delay days to the second incumbents.

The expert now makes the case that the initial 200 days caused, no longer apply and these are replaced by the new delay causes and the initial forms of causation are now relieved of liability:

| Groundwork delays | 75 days |

| Structural steelwork delays | 75 days |

| Facade delays | 50 days |

The arbitrator would now ask himself whether it is correct that these delays are no longer considered as causative of a delay and would expect the expert to provide sound reasoning.

The expert in anticipation of this ought to demonstrate the cause and effects of the accrued delays, in a linear manner, to relieve the reliance on the arbitrator’s understanding.

The representation of the accrued delay and causation by the expert would demonstrate visually the compounded effect of the delays on the projects. This allows the dissemination of the issues of concurrency, dominancy and apportionment.

Where a number of delays run concurrently, as they must, the expert must begin to consider their imposition on the project delay.

The issues of potency and dominancy ought to be in the expert’s mindset and how to demonstrate these.

Often the expert simply expects the programming art and conclusions to be accepted and understood by the arbitrator. But in reality, the questions have already been asked:

- Where the expert simply accepts the progress programmes of the claimant, the delay analysis in the windows may be based on hearsay evidence.

- If there is no probative test of the progress reports and programmes that are produced by specific reference to facts and evidence, then they will be in danger of having little value in the expert opinion.

- If the expert simply removes previous delays to rely on a specific cause of action and one that removes its own culpability, then again, the analysis begins to fail.

- Where certain of the claims fail on merit and require removal from the analysis, the resultant effect ought to be considered.

Conclusions

In summary, while delay analysis is a complex subject and can be extremely theoretical, the successful and respected expert will have careful regard to facts and events that happened during the project. Critical to successful demonstration of entitlement will be the consideration of all the facts and activities that led to the delay. Clear demonstration of cause and effect will ensure acceptance of a claim – a more impressionistic approach will often lead to failure and frustration whether submitting to a contract administrator, judge, arbitrator or other tribunal.